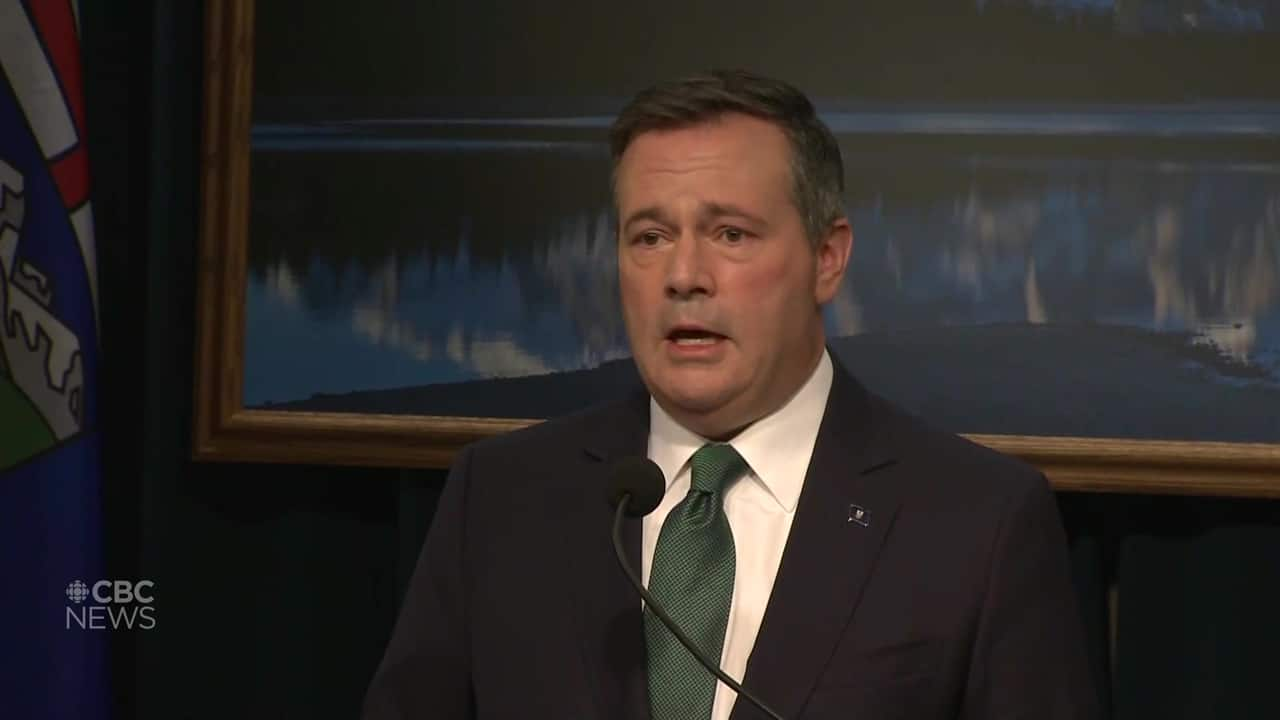

What Jason Kenney claims about the oil industry vs. what the evidence says

[ad_1]

If there’s one topic Jason Kenney loves to talk about, it’s the oil industry.

And understandably so.

Oil, of course, is a major driver of Alberta’s economy. Despite tens of thousands of layoffs in recent years, the industry remains a massive employer. Until royalties shrivelled in the wake of the latest downturn, it was a substantial source of direct revenue for the provincial treasury. Hopes of ever balancing Alberta’s budget remain pinned on those royalties bouncing back, to some degree, at some point in the future.

So it’s no wonder the Alberta premier makes oil such a frequent topic of conversation.

But some of Kenney’s recent comments about the size, scale and state of the industry have raised eyebrows among people who closely follow these things. And comparing the premier’s rhetoric to the available evidence doesn’t always result in a perfect match.

Kenney has made some strong claims that, when scrutinized, appear less than accurate. When traced to their source, some of the numbers he likes to cite seem exaggerated, cherry-picked or rounded up. Others look better, however, under the light of external evidence. And much of that evidence comes from one of Kenney’s frequent foils — the federal government.

In general terms, there’s little doubt about the overall point the premier so often makes: oil continues to be a major component of not just the provincial economy but Canada’s economy as well. And despite the headwinds the industry faces, it will likely remain that way for some time to come.

The devil comes in the details.

Here are some recent examples.

Claim: ‘Canada’s largest industry — the energy sector’

Kenney made this claim, most recently, after the federal throne speech.

In a written statement issued to the media, the premier said the speech failed to recognize “the crisis facing Canada’s largest industry — the energy sector that supports 800,000 jobs, directly and indirectly.”

There’s a lot to unpack here.

First off, the language. “Energy” and “oil” are often used interchangeably in Alberta, but Kenney’s choice of words here is important. What, exactly, does he mean by “the energy sector,” and where is he getting these numbers from?

The premier’s issues manager, Matt Wolf, referred that question to Alberta’s energy ministry, who referred detailed questions to the Canadian Energy Centre (commonly known as the “war room“), which said it took its definition of “energy” from Natural Resources Canada.

“This includes oil and gas extraction and support activities, utilities, petroleum and coal products manufacturing and pipelines, warehousing and transportation support activities, renewables and utilities,” Mark Milke, the Canadian Energy Centre’s research director, said in an email.

Specifically, he cited this section of the Natural Resources Canada website, which indeed supports Kenney’s claim about jobs: “In 2018, Canada’s energy sector directly employed more than 282,000 people and indirectly supported over 550,500 jobs.”

Add that up, and you get 832,500 jobs — slightly more than the 800,000 figure Kenney cited.

But does that make the energy sector Canada’s largest industry?

It’s more difficult to see how the premier arrives at that conclusion, as other industries employ far more people. Nearly 1.6 million people worked in the manufacturing sector last year, according to Statistics Canada data. And more than 2.8 million people worked in wholesale and retail trade.

Of course, there’s more to an industry than the number of people it employs and, in terms of productivity, fossil fuels have made an outsized contribution to the national economy. Mining, oil and gas contributed more than $200 in value added to Canada’s GDP per hour worked, according to a 2016 paper by University of Calgary economist Trevor Tombe, making it by “far and away the most productive sector in the Canadian economy.”

When you add up all the direct and indirect economic activity of the “energy sector” as a whole, it represented 11.1 per cent of Canada’s total GDP in 2018, according to Natural Resources Canada’s Energy Fact Book.

So does this make it Canada’s largest industry?

It’s hard to say definitively. Not only are there different ways of defining the industry; there are also different ways of measuring and reporting GDP.

According to this data from Statistics Canada and its definitions, the “energy sector” accounted for 9.4 per cent of GDP in 2018, which was less than manufacturing (10.4 per cent) and real estate (12.6 per cent). And remember, the “energy sector” includes more than just fossil fuels. Taken alone, mining and oil and gas extraction were 8.1 per cent of GDP.

Crude oil, by itself, accounted for 2.8 per cent of national GDP, according to the Natural Resources Canada accounting.

In the past, Kenney has often referred to oil as Canada’s largest export industry, which is certainly borne out by international trade data.

When speaking off the cuff, this could perhaps be accidentally shortened to just “industry.” But in written remarks like Kenney provided on this topic, it’s harder to see how the claim is justified.

Claim: ‘Even conservative estimates … show the global demand for oil increasing over the next 20 years’

Kenney made this claim in a recent tweet.

And on that point, Sara Hastings-Simon says the premier is simply wrong.

“That’s not what the estimates say,” said Hastings-Simon, who works as a senior researcher with the Payne Institute for Public Policy at the Colorado School of Mines and a research fellow at the University of Calgary’s School of Public Policy.

There is “obviously a lot of uncertainty” in the various models that estimate future oil demand, she said, and there are a wide range of educated guesses about when peak oil consumption will arrive.

“But if you look at the set of the most ‘conservative’ estimates — meaning, the closest the peak could be — there are estimates that the peak has already passed,” she said.

BP Energy, notably, came out with one of those estimates in mid-September. In one of three scenarios the company examined, which assumes more aggressive climate-change actions by governments around the world, 2019 marked the year the world consumed the most oil.

The International Energy Agency (IEA), which Kenney has described as “the leading global think-tank on these issues,” has also come out with recent estimates which suggest peak oil could be coming soon, if it hasn’t already arrived.

The IEA’s World Energy Outlook 2019 outlined a future in which “oil demand growth is robust to 2025, but growth slows to a crawl thereafter.” This was under its “stated policies scenario,” which assumes “existing policy frameworks and today’s announced policy intentions” from governments around the world.

Under its “Sustainable Development Scenario,” which assumes an “unprecedented scale, scope and speed of changes in the energy landscape,” the IEA sees “a very different picture,” one in which “demand soon peaks” and drops to less than 67 million barrels per day in 2040. That’s down about 33 per cent from 2019 levels.

Kenney himself, seemed to contradict his own tweet. When he addressed the same topic in person at a press conference in late September, he selected more nuanced words.

WATCH | Kenney discusses future oil demand:

The Alberta premier talks about how much oil the world might need in the future. 0:56

“Every major expert in energy consumption projects that there will be substantial consumption and demand for oil and gas for decades to come,” Kenney told reporters.

You’ll note the different phrasing here: There’s quite a difference between decades of “substantial” consumption and decades of “increasing” consumption.

Kenney went on to acknowledge that the IEA’s “most bearish scenario” sees global oil demand shrinking substantially by 2040.

Claim: ‘The transportation sector is not where most oil is consumed’

Kenney made this claim in response to a question about how demand for Alberta oil might be affected by plans in places like California to ban the sale of new gasoline and diesel cars by as early as 2035.

“First of all, the transportation sector is not where most oil is consumed,” the premier said at the same press conference.

WATCH | Kenney discusses oil consumption:

The Alberta premier makes an assertion about how much oil is consumed for transportation purposes. 0:07

The U.S. Energy Information Administration says otherwise.

“The transportation sector accounts for the largest share of U.S. petroleum consumption,” the EIA says on its website.

To be precise, it estimates that transportation accounted for 68 per cent of end-use U.S. petroleum consumption in 2019.

In Canada, the numbers are similar. The Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers says 65 per cent of oil is used for transportation, “including gasoline, diesel and jet fuel.”

And globally, transportation accounted for the majority of liquid fuel consumption in 2018, according to data from BP Energy.

Overstating vs. underestimating

Some of these claims in the recent press conference could have been genuine mistakes. Kenney was speaking in an impromptu way, in response to a reporter’s question, at the tail end of a lengthy series of remarks. It’s harder to understand the numbers in his written statements the same way.

But even if Kenney is exaggerating some of these figures, a close look at the data makes clear the magnitude of the oil industry in Canada. And the general point the Alberta premier is trying to make is not out of line with what the federal government is doing with its own reports: both are highlighting the significant economic role the industry plays.

Natural Resources Canada isn’t the only federal organization pointing this out. Just last week, the Parliamentary Budget Office released its latest economic and fiscal outlook, which included an economic damage report, of sorts, on the first half of 2020.

It blamed “the sharp contraction in the Canadian economy” on the public-health restrictions due to COVID-19 and “the record collapse in oil prices.”

Taken together, the PBO says the “pandemic and oil price shocks” are expected to have “a permanent impact on the Canadian economy,” pushing real GDP 3.6 per cent lower by the end of next year, and 1.6 per cent lower by the end of 2024, compared to its outlook from November 2019.

Oil may not be largest industry in the nation, but it’s big enough to drag down the national economy when it goes through tough times. It may not be the largest employer, but it’s the most productive. Demand for oil may not grow for much longer, but the world will almost certainly consume tens of millions of barrels daily for decades to come.

So while the Alberta premier may overstate the importance of the oil industry in Canada, it’s important to not underestimate it, either. At the same time, a realistic assessment of its future may foresee better days ahead while also expecting the best days have likely already come and gone.

[ad_2]

SOURCE NEWS