How COVID-19 worsens Canada’s digital divide

[ad_1]

Chawathil First Nation lies just 600 metres north of the Trans-Canada Highway in southwestern B.C., but it feels much more remote when you try to log onto the internet from here.

That’s apparent when, from behind a Plexiglas barrier at the band office, finance manager Peter John attempts to run an online speed test to measure the dial-up connection.

It takes nearly two minutes for the page to load, and once it does, the meter shows the download speed is an agonizingly slow one megabit per second (Mbps)

With that kind of setup, it means students struggle with online classes, and the band can’t hold video meetings.

“Everything they could get out of the internet, they’re not able to really get it because it’s not there,” John said.

When the pandemic thrust most school, work and services online, it further highlighted not just how essential the internet has become but also the urban-rural divide around access.

The CRTC recommends that every household have access to broadband with download speeds of at least 50 Mbps, and the federal government has set a goal to have Canada-wide broadband by 2030.

According to the CRTC, nearly 86 per cent of households overall have that level of service currently, but in rural areas only 40 per cent do. In First Nation communities, it’s estimated that just 30 per cent of households have internet connections with the recommended speed.

And even while the connections in remote areas are often slower, the service tends to be more expensive.

Deanna John, a child-and-family advocate as well as a band councillor for Chawathil First Nation, said those in the community who have internet pay around $130 dollars a month, while others come to the band office after hours to see if they can tap into the building’s network. Some choose to take a 35-minute bus ride to Chilliwack to use the Wi-Fi at a coffee shop, she said.

The limited internet has made it harder for residents to get health care.

John said the community’s doctor, who used to come about once a week before the COVID-19 pandemic, is unable to see patients online. Some residents have instead been driving to the nearby town of Agassiz for appointments.

“I would like [the internet] to be up and available … so we’re not struggling with our kids falling back on education and that we’re actually connecting our people to the mental health specialists out there,” said John.

John said the band had been speaking with Telus about upgrading the internet but was told it would cost tens of thousands just to increase the speed at the band office.

Federal funding

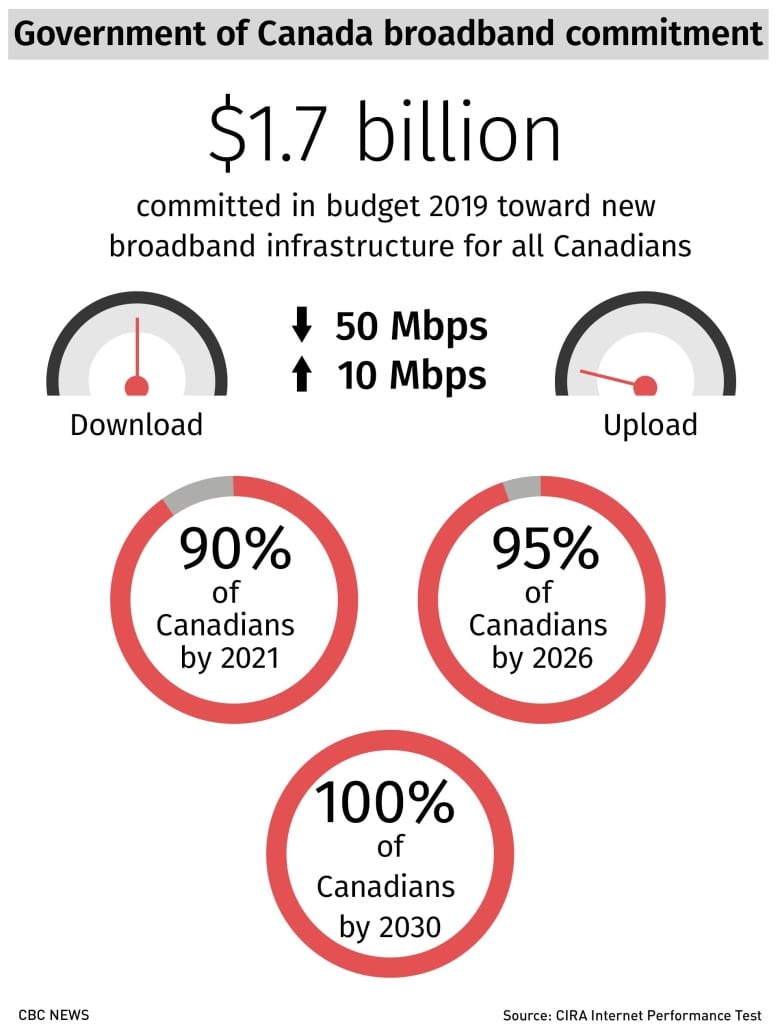

In the 2019 budget, the federal government announced $1.7 billion in funding to support high-speed internet in remote and rural areas: $1 billion is slated for a Universal Broadband Fund, for extending internet infrastructure; $600 million for satellites, which can help connect some of the most remote communities; and $85 million to top up an ongoing program called Connect to Innovate which helps fund specific community projects in rural and First Nation communities.

The Canadian Internet Registration Authority (CIRA), a not-for-profit organization that manages the .ca domain and advocates for better internet service, says it is currently working with about 400 rural communities to map connection speeds neighbourhood by neighbourhood. The organization also runs a yearly $1.25-million grant program to help communities invest in projects including internet infrastructure.

“Canada’s internet service providers have passed over a lot of communities because they’re just not worth it financially,” said Josh Tabish, corporate communications manager with CIRA.

“This is where we need the government to step up.”

He said experts believe it will cost up to $6 billion to roll out broadband across Canada and he believes the federal government needs to act faster. The application for the Universal Broadband fund has yet to open.

Tabish said about one in 10 Canadian households have no internet connection whatsoever, and the pandemic has exacerbated the gap in connectivity between rural and urban areas. He said high-speed internet has become even faster in cities, while it has plateaued in remote areas.

In the meantime, he said, those without it struggle with daily life.

Spotty satellite connection

In the hamlet of Ryder Lake, residents have been pleading for better internet for years. The community is made up of sprawling acreages and farms that stretch up a lush green mountainside in B.C.’s Fraser Valley.

The landscape was one of the reasons Sheri Elgermsa and her family of six moved here despite the fact that only satellite internet is available. When CBC News visited, her family was only getting about nine Mbps download speed.

WATCH | Family of 6 schedules online time due to slow speed, spotty service

“When we moved up here eight and a half years ago, the internet … was a social thing. It was nice-to-have,” Elgersma said.

“Now it’s become essential.”

When schools were closed back in the spring and classes moved online, Elgersma had to sit down with her four children and work out a schedule, as the internet connection would only allow one person to be online at any given time.

If there were any classes overlapping, she said, she would have to pick one over another.

Her oldest son, Elijah, 18, was often the priority, as he was wrapping up his final year of high school. He is now enrolled in a university program and has online classes two days a week, but even with no one else in the house allowed online at those times, the internet is still an issue.

“All of a sudden it kind of goes frozen and I miss half the stuff,” Elijah said.

“It’s a little bit frustrating.”

[ad_2]

SOURCE NEWS