Why COVID-19 cases are surging across Canada and what needs to be done

[ad_1]

This is an excerpt from Second Opinion, a weekly roundup of health and medical science news emailed to subscribers every Saturday morning. If you haven’t subscribed yet, you can do that by clicking here.

Six weeks ago, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau said the country was at a “crossroads” in the COVID-19 pandemic.

Now, with cases spiking in regions that were practically untouched by the virus in the first wave, it appears we’ve taken a wrong turn.

There have been more than 100,000 new cases of COVID-19 and over 1,000 more deaths in this country since Trudeau made those comments.

The percentage of COVID-19 tests across the country that have come back positive has also grown by more than 235 per cent — from 1.4 per cent in mid-September to 4.7 per cent in the past week.

So where did Canada go wrong?

Experts say a mix of insufficient public health measures and complacency brought us to where we are today and we need to act quickly to turn things around — or at the very least prevent them from getting worse.

Canada ‘failed’ to follow lessons

South Korea taught us that by building up a robust test, trace and isolate system, it’s possible to control the spread of the coronavirus without subjecting your population to large scale lock downs.

New Zealand locked down quickly, then shifted to a South Korean model focused on building up testing, tracing and isolating cases.

But Australia learned the hard way in the second wave that, if you let the coronavirus spread unchecked for too long, tough action is needed to keep it under control through further lockdowns and strict public health measures.

“The lesson across all of the world is that the places that do the best are the ones that act hard and early,” said Raywat Deonandan, a global health epidemiologist and an associate professor at the University of Ottawa.

“That’s where we failed.”

Experts say Canada, comparatively, has seemingly not yet learned these lessons.

“In Canada, we never set clear goals and so we opened up without having built a solid test, trace isolate strategy,” said Dr. Irfan Dhalla, vice-president of physician quality at Unity Health in Toronto.

“We didn’t follow the indicators closely enough and now we’re paying the price. The good news is we’re not paying nearly as bad a price as people in some other countries are paying, but it would be a big mistake to compare ourselves to the worst countries in the world.”

Ontario ‘highly unstable’

In Ontario, there are currently almost 150 outbreaks in long-term care homes, the seven-day average of cases has grown to nearly 1,000 and the largest number of COVID-19 deaths in a single day happened this week.

“The situation we find ourselves in right now is highly unstable,” said Dhalla, who is also an associate professor at the University of Toronto who sits on provincial and federal committees related to the COVID-19 response.

“It wouldn’t take much to put us on a path towards the kinds of outcomes we’re seeing in Belgium, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, many American states.”

But with over half of Ontario’s cases with no known link to previous cases and community transmission running rampant, experts say the province doesn’t have a clear enough view of the situation.

“We don’t understand how many people are infected. We know that it’s a lot, but we really don’t know the magnitude,” said Dr. Andrew Morris, a professor of infectious diseases at the University of Toronto and the medical director of the Antimicrobial Stewardship Program at Sinai-University Health Network.

“If this were an iceberg, we don’t know how much is above or below water.”

Despite this, Ontario is moving to ease restrictions on much of the province, even without hitting its full testing capacity and contact tracing and isolation of cases not functioning in hot spots like Toronto due to the sheer volume.

“We know in Ontario that 1,000 cases per day is not a sustainable situation. We have too many outbreaks in hospitals, we have too many outbreaks in long-term care homes,” he said.

“We have to bring the number of cases down from 1,000 a day back down to something like 50 or 100 per day. And when we get back down there, we need to have a test, trace, isolate strategy that works.”

WATCH | Ontario’s restrictions system under fire:

Ontario has announced a new tiered system for triggering COVID-19 restriction, but critics say the sky-high thresholds won’t stop the virus from spreading across the province. 1:59

Manitoba suffered from ‘complacency’

Manitoba went from one of Canada’s shining examples of how to successfully manage the spread of the coronavirus, to facing its single worst outbreak.

“Some of us lost our way, and now COVID is beating us,” Premier Brian Pallister said Monday. “Perhaps we were cursed by our early success.”

It was that early success that caused the province to let its guard down, leaving it vulnerable to a surge in cases when the virus re-entered the community.

“We had a very good proactive response in early spring. We shut things down very quickly, everybody seemed to be quite on board and cases receded,” said Jason Kindrachuk, an assistant professor of viral pathogenesis at the University of Manitoba in Winnipeg and Canada Research Chair of emerging viruses.

“And that, probably, in some ways, fed a complacency across all levels.”

Kindrachuk said that because Manitoba didn’t bear the brunt of COVID-19 that other regions of the country had, it lost focus on the need to prepare for the future.

“Then everything hit at the perfect time — we had exponential growth, we had community transmission, we likely had superspreading events, we had outbreaks that occurred in long-term care facilities,” he said.

“The worst of the worst that could have happened, did happen.”

Alberta faces ‘tipping point’

Alberta shattered COVID-19 records on Thursday, recording what health officials described as “about 800” new cases after specific numbers were unavailable due to technical problems with the province’s reporting system.

It’s another province that saw low case numbers slowly rise after a lull in the summer, but waited to act on imposing stricter restrictions and now faces the prospect of a worsening second wave.

Dr. Lynora Saxinger, an infectious diseases specialist and an associate professor at the University of Alberta’s faculty of medicine, called the situation “profoundly disturbing.”

“You can have things simmering along, and then it just starts to boil over — there’s a tipping point, and it starts to change,” she said.

“And when that happens, what we’ve seen across the world, is the actions in that early phase make a really big difference.”

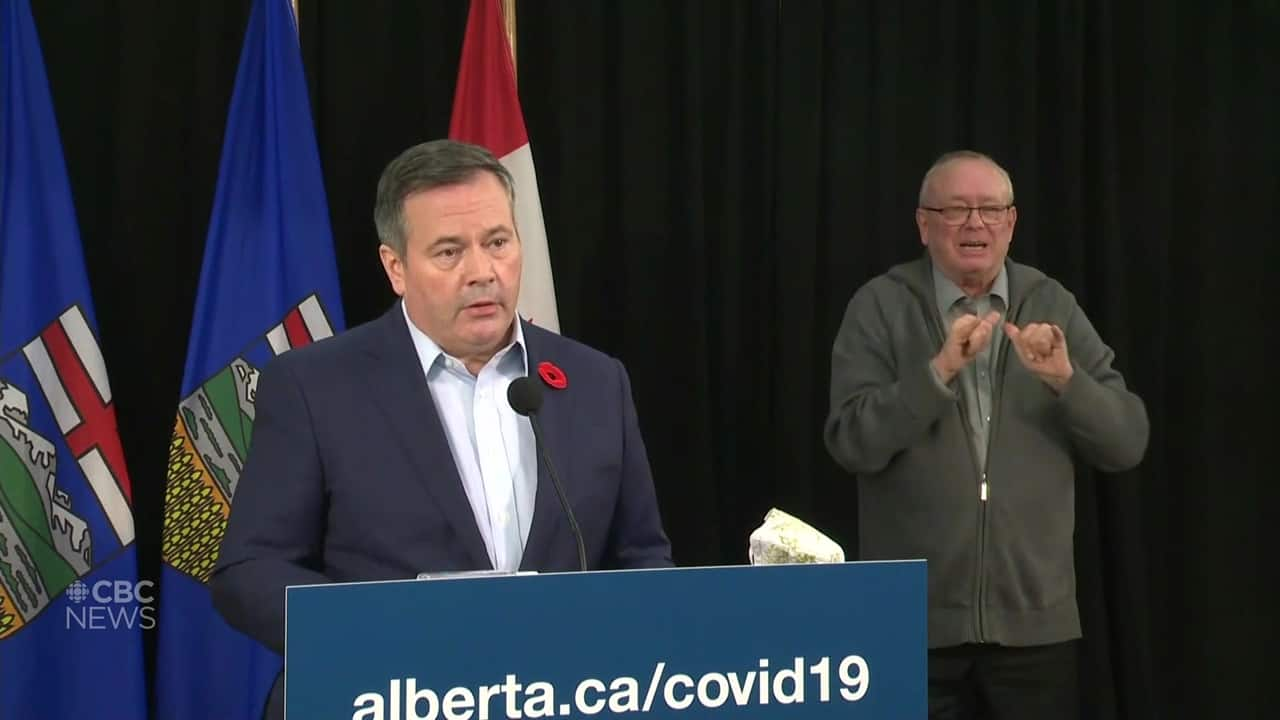

Alberta Premier Jason Kenney rejected the call for stricter public health restrictions this week, the same time a record 171 people were hospitalized with COVID-19, 33 of them in ICU, and nine more people died.

“We’ve seen other jurisdictions implement sweeping lockdowns, indiscriminately violating people’s rights and destroying livelihoods,” Kenney said Friday, rejecting the call for further measures to curb the spread of the virus.

“Nobody wants that to happen here in Alberta.”

Saxinger said Alberta should look at emulating a “circuit breaker” model of controlling the virus from the U.K., focused on brief lockdowns that can interrupt transmission and reverse rising case numbers quickly if rolled out successfully.

WATCH | Stop gatherings in homes, Kenney urges Albertans:

Premier Jason Kenney is calling on Albertans to not host parties or large family dinners and is expanding the 15-person limit on social gatherings to all communities on the province’s COVID-19 watch list. 2:42

“There’s a certain part of the population that’s just not really paying attention as much anymore,” she said. “So you might need to have that short, sharp, lockdown that’s visible to actually really get the whole population re-engaged.”

Saxinger said she’s worried Alberta is past the point of “targeted” restrictions due to rising community transmission and inadequate contact tracing and is being “surged under” by new cases and hospitalizations.

“I’m really afraid that it could take off in a really bad way,” she said. “A lot of us are very anxious right now and the hospitals are already stressed.”

Record numbers in B.C.

British Columbia was praised for its vigorous test, trace and isolate approach and became a global model for how to effectively control the spread of the virus, but could risk jeopardizing the progress it’s made if it doesn’t regain control of a surge in cases.

The province hit a record high COVID-19 case numbers two days in a row this week, with 425 on Thursday and 589 on Friday adding to the 3,741 active cases in the province currently.

Unlike Quebec, which saw its cases surge a month after school started and has been struggling to regain control, B.C. has largely seen outbreaks in community settings.

“Most of the transmissions are through gatherings … superspreader-type events that happen with lots of people in a room,” said Dr. Srinivas Murthy, an infectious disease specialist and clinical associate professor in pediatrics at the University of British Columbia.

“I think our lack of attention to that, and how we can target where we know those large-scale transmission events happen, was probably not as rigorous as it could have been.”

Murthy said new public health restrictions focused on limiting the size of gatherings, mandating masks in health-care facilities and threatening businesses with closures for not following guidelines will hopefully drive down the numbers and avoid lockdowns — but it will take time.

“So far we’ve been able to, with pretty rigorous data collection, follow up and trace and isolate most of the cases in the superspreading events that have happened,” he said.

“But if there is an increased, unlinked case number in the community that’s unable to be traced and isolated — then obviously large-scale social distancing would be probably the next step.”

Atlantic bubble needs vigilance

The Atlantic bubble, a success story for curbing COVID-19 spread, is another model that other parts of the country can learn from.

The four Atlantic provinces imposed tight restrictions on points of entry, moved quickly to clamp down on new outbreaks of COVID-19 and focused on aggressive contact tracing and isolating.

But epidemiologist Susan Kirkland said the recent surge in cases in parts of Canada that weren’t hit as hard in the first wave is a stark reminder of the need for the region to avoid letting its guard down.

“We have to be constantly vigilant,” said Kirkland, head of public health and epidemiology at Dalhousie University in Halifax. “As long as COVID isn’t introduced, we’re OK. But the minute it is, the environment is rife for it to spread very, very quickly.”

The Atlantic provinces have so far avoided rampant community spread of the virus with unknown origins, but Kirkland says rising numbers across the country show it could happen anywhere — even the North.

Nunavut confirmed its first case of COVID-19 on Friday and while health officials say contact tracing is currently underway in the community, the territory’s rapid response team is “on standby to help manage the situation should it become necessary.”

WATCH | No sign of bubble bursting:

Like an extended family, the four Atlantic provinces have walled themselves in, creating measures to restrict outsiders and COVID-19 cases. So far, it’s worked and there doesn’t seem to be much of a rush to burst the Atlantic bubble. 5:09

Kirkland said Atlantic Canada has much more in common with the North than it does with more populous provinces like Ontario and both regions face an uncertain future.

“Part of the reason that we’ve done so well is because we are isolated,” she said, adding that they have also benefited from strong public health messaging and a compliant public.

“But the minute we have community spread, we’re again in that situation where we’re putting ourselves at big risk. So it’s hard to be complacent.”

To read the entire Second Opinion newsletter every Saturday morning, subscribe by clicking here.

[ad_2]

SOURCE NEWS