COVID-19 mortality rate higher in neighbourhoods with more visible minorities, says StatsCan

[ad_1]

Residents of communities home to more visible minorities had a higher likelihood of dying from COVID-19 in Canada’s three largest provinces, according to Statistics Canada, in a trend health experts say underscores the need for provinces such as B.C. and Quebec to improve their data collection on race and mortality.

A report issued by StatsCan late last month looking into COVID-19 mortality rates in “ethno-cultural neighbourhoods” found communities in B.C. that were home to more than 25 per cent visible minorities had an age-adjusted COVID-19 mortality rate that was 10 times higher than neighbourhoods that were less than one per cent visible minority.

In Ontario and Quebec, neighbourhoods with large visible minority populations had age-adjusted mortality rates three times higher than the general public.

That COVID-19 deaths in B.C.’s ethno-cultural neighbourhoods are ten times higher than comparable rates for Canada’s broader population could be partially linked to a lower general death rate in the province.

As of Monday, 299 people with the virus had died in B.C., out of more than 11,000 deaths across Canada.

The Statistics Canada analysis was compiled when B.C. had fewer than 200 coronavirus deaths. But the analysis is part of a growing body of literature showing that visible minority communities in Canada have been hit harder by the virus than the general population.

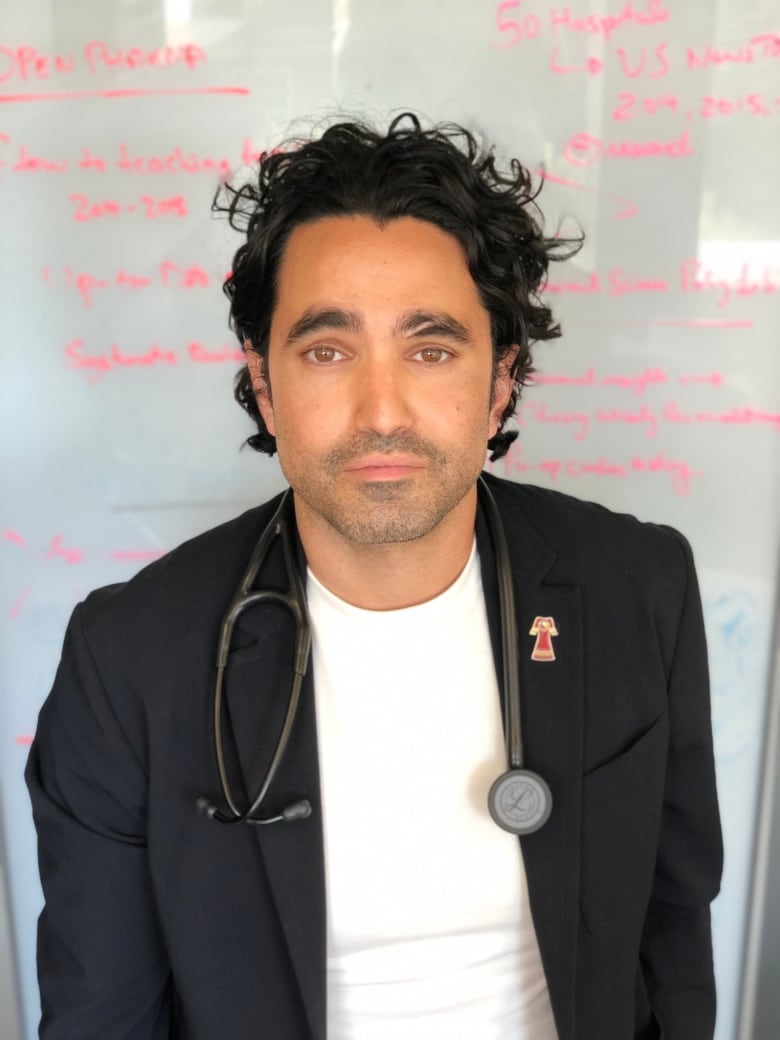

Dr. Andrew Boozary, the executive director of Social Medicine and Population Health at the University Health Network in Toronto, said it’s important to have specific, reliable data so affected populations can be protected.

“We’ve not been a leader on that front and it has been awfully expensive in not allowing our response to be as precise as we hoped, but also not allowing us to galvanize the response as quickly as we should have.”

‘Extremely important to be collecting that data’

Unlike Ontario, Quebec and B.C. are still not collecting the data that would identify which communities are most at risk, or why they are at risk, despite repeated calls to do so.

One of those calls is from B.C.’s Human Rights Commissioner, Kasari Govender, who said data on COVID-19 deaths and ethnicity is urgently needed to understand why members of different communities who get the coronavirus may be dying at higher rates and to establish how to address the problem.

“It’s, I think, extremely important to be collecting that data,” said Govender, whose office put out a report in September about how data on ethnicity, among other things, could be collected in B.C. “Now, we’re not going to get the data overnight. So the sooner we start collecting, the sooner we can work and put in place good, strong policies.”

Provincial Health Officer Dr. Bonnie Henry supports collecting this data, B.C. Health Ministry spokesperson Stephen May said in a statement, but “due to the surge in cases and demand on Public Health resources, data on race is not currently being collected at the point of care, with the exception of data on Indigeneity.”

B.C. is working with the federal government on a national framework to collect such data, May added.

Other jurisdictions are not waiting for Ottawa.

More data in Ontario

Ontario has been collecting data on socioeconomic indicators, including ethnicity and income, for several months.

The City of Toronto has released such data, and the results have brought to light serious concerns about structural racism and how it affects health outcomes, said Dr. Boozary.

“We see more than 80 per cent of cases happening in visible minorities. And we see over 50 per cent to 60 per cent of the cases in low-income households,” he noted.

“This isn’t about a deficiency in people or communities. These are structural deficiencies that we’ve allowed to take place because of structural racism, because of structural discrimination toward certain populations.”

In cities where neighbourhood or ethnicity-specific data has been released, it is known which groups have been most affected.

In Toronto, the data showed the Black, South Asian, Arab, Southeast Asian and Latin American communities were over-represented among COVID-19 cases. Whites and East Asians were under-represented. It also showed households with incomes under $50,000 to be over-represented among confirmed cases.

Quebec does not collect ethnicity or income data on confirmed COVID-19 cases, but Montreal Public Health released neighbourhood-level data, which CBC News compared with Census data from 2016 on visible minority status, income level and housing suitability.

CBC’s analysis found neighbourhoods with higher proportions of Black people and overcrowded households had also registered the most COVID-19 cases in Montreal.

No data in B.C.

In B.C., it’s not known which groups are most affected, because the province is not collecting the data.

There has been a disproportionate increase in COVID-19 cases among B.C.’s South Asian population, Dr. Henry told a group of Punjabi language media outlets last week. She emphasized the spread of the virus does not have to do with ethnicity, but with situations, such as indoor gatherings and events, that allow it to spread.

Govender said there are likely different factors at play for different communities. Filipino workers, for example, are more likely to be in front-line, public-facing jobs such as caregiving that can’t be done from home. Indigenous populations, who are not included in Statistics Canada’s definition of visible minority, may face challenges in getting access to the health care they need, she said.

“So there might be different reasons. And we need to understand those reasons in order to be able to address the problems effectively.”

Boozary said the fact that COVID-19 is more prevalent among low-income and racialized communities should not come as a surprise.

“When you look at anything from diabetes to cancer to some of the heart and lung conditions that we have, it has always been highly concentrated amongst people living in poverty and in racialized communities,” he said.

“Most everyone in public health could have predicted where COVID was going to be most concentrated because of the structural vulnerabilities, because of the impossible situations that certain populations and neighbourhoods are in.”

One of those situations is overcrowded housing, a significant problem in some of B.C.’s most affected regions.

Lack of space

Boozary and other researchers interviewed by CBC News all said unsuitable housing, defined by Statistics Canada as dwellings that do not have enough bedrooms for the size and composition of the household, is an indicator of COVID-19 risk because it makes it difficult or impossible for an infected family member to isolate.

The neighbourhoods with the highest proportions of overcrowded households in 2016, the most recent year for which Census data is available, were mostly in the north end of Surrey, about 45 minutes east of Vancouver, which is home to a high proportion of South Asian residents and new immigrants.

Surrey is also the city with B.C.’s highest number of COVID-19 infections.

Health officials in B.C. have not released COVID-19 data that is any more granular than city-level, so it’s not known where specifically the most cases have been reported.

Khim Tan is the deputy executive director of employment and immigrant services with Options Community Services Society, which does community outreach in north Surrey.

Tan said finding housing for newly-arrived immigrant families of sometimes eight or 10 people has been a challenge for years. Many, she said, wind up in basement suites in Newton, Whalley or Guildford, because those areas are more affordable and home to immigrant communities from many countries.

COVID-19 has brought the issue of insufficient space into stark focus.

“What we’re seeing is that many newcomer families, especially the large families … don’t have the luxury of moving to a bigger space when a family member gets infected.”

Tan said Fraser Health has done a good job of creating and translating culturally specific health information, such as how to put a mask on with a turban or hijab, or how to safely celebrate Diwali.

And Dr. Henry has cautioned people living in intergenerational households to think about seniors or others who may be vulnerable when considering riskier activities such as indoor fitness classes.

But public health officials have been silent or vague on how to isolate or minimize transmission in households where there isn’t enough space for the number of people, or what the concept of a “safe six” means for a family of 10.

When CBC News asked the BC Centre for Disease Control what guidance was available for people in these situations, we were referred to a tip sheet for residents of apartments and multi-unit buildings.

“We have so many families living in very limited spaces and obviously there has been COVID cases. But one thing we have found … is that families are resilient. They find ways to manage. They find ways to isolate the family member that might be sick or with COVID within tight quarters,” she said.

“The support is there in terms of bringing food to a family that may not be able to leave the house as much because they have to self isolate. So we’ve seen amazing behaviour shifts.”

[ad_2]

SOURCE NEWS